Bethany Mattson, ND

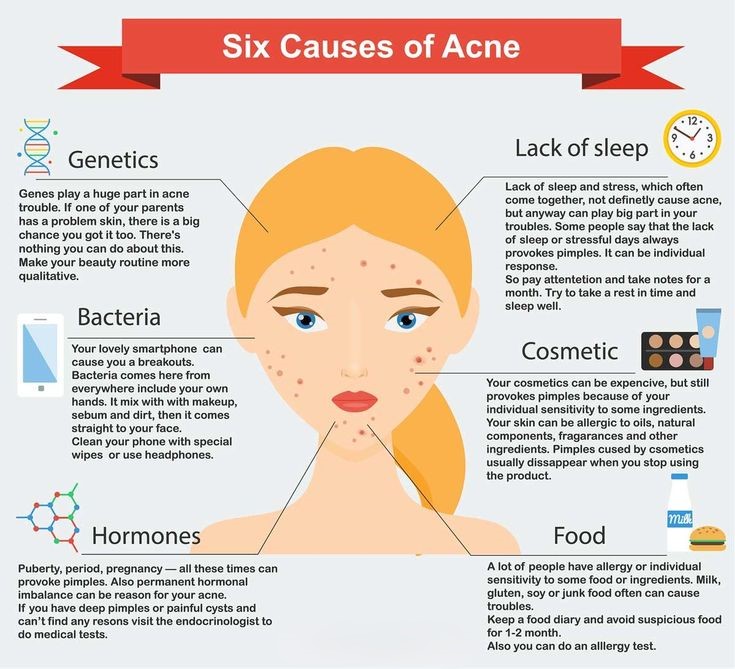

Oftentimes patients view acne as something that needs to be fixed with a better face wash, or by starting antibiotics in their teenage years. However, the holistic approach to managing acne is multifaceted and includes a combination of broad lifestyle changes and supplemental or topical methods. Acne should be recognized and conveyed to patients as a chronic issue that will likely require long-term management. The comprehensive approach to acne often includes patient education about the many contributing factors to acne, including genetic, hormonal, diet, and lifestyle implications.

Although there is a genetic component to the development of acne, several key underlying triggers should be evaluated, including hormonal changes, elevated systemic inflammation, stress, and lifestyle factors. A detailed intake should include family history of acne, smoking status, sleep habits, weight management, and dietary intake. Hormonal implications of acne are wide and are rooted in elevated androgen production that require workup through clinical signs and laboratory findings.

EVALUATION:

Changing Hormone Levels

Although some degree of hormonal impact on acne production is expected, especially during puberty, hormonal implications can extend far beyond increased sebum production and cellular growth activity. When working with a patient with acne, the first goal is to rule out underlying neuroendocrine disorders that may be presenting with acne, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in females. Distinguishing between an underlying neuroendocrine disorder compared to another trigger of acne helps providers uncover the true root cause of imbalance.

Clinical signs and symptoms of elevated androgens to evaluate for include:

- Hirsutism in females

- Cystic acne along the chin and jawline

- Hyperpigmentation of the skin

- Alopecia

- Amenorrhea/anovulatory cycles

- Increased muscle mass

- Decreased breast size

It is important to accurately test for elevated androgen production beyond free and total testosterone levels. The addition of key lab markers including 5a-androstendiol, DHT, luteinizing hormone, anti-Mullerian hormone, and DHEA-sulfate can help accurately diagnose hyperandrogenemia. Additional lab markers in the evaluation of acne should also include 17-OH progesterone, insulin, HbA1c, prolactin, and a full thyroid panel to assist in the differential diagnosis process.

Even in the absence of an underlying medical condition such as PCOS, the sebaceous gland is now being studied as a neuroendocrine organ, which is impacted by a wide variety of hormones including corticotropin releasing hormone, cortisol, melanocortins, histamine, IGF-1, and androgens. The role of stress and inflammation are interconnected with these hormonal changes and can help guide both evaluation and treatment of acne.

Chronic Stress and inflammation

There is a correlation in the research between elevated stress and acne breakouts. During an acute stress response, cortisol and androgens are released and stimulate cellular proliferation and release inflammatory cytokines. An older model of acne pathogenesis included separating inflammatory from non-inflammatory types of acne. This framework is now shifting towards all acne having a component of underlying inflammation present. Systemic inflammation is impacted by stress hormones and lifestyle factors including diet.

TREATMENT:

Dietary Interventions

When initiating treatment for acne, the comprehensive approach often involves treating the patient with diet and lifestyle modifications as a priority, emphasizing supporting healthy cell catabolism, cell regulation, and management of cellular growth. The treatment for each patient is individualized based on pertinent risk factors but may include dietary changes including limiting dairy, chocolate, and incorporating lower glycemic index foods.

There are several key metabolic pathways that have been associated with acne including mTORC1, Fox01, and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1). The standard western diet has been associated with increased acne because of its effects on all three metabolic pathways. The mTORC1 and IGF-1 pathways are what fuel cellular growth and “turn on” the acne process and are stimulated by components of the standard western diet including higher carbohydrate content, refined sugars, and unhealthy fats. Conversely, the Fox01 pathway is associated with decreased acne progression and is inhibited by the standard western diet, leading to higher acne rates.

Diets higher in carbohydrates and general excess caloric intake both have been linked to increased IGF-1 levels. Dairy consumption also increases IGF-1 levels and activates the mTORC1 pathway. Dairy does not have to be avoided completely, however. Research shows that prioritizing full fat dairy sparingly (about 3-6 servings per week) is not associated with increased acne development.

As with many health conditions, the Mediterranean diet is linked with reduced acne rates, especially those that prioritize nuts and fish intake. Many foods can be added to a diet to inhibit mTORC1 activation including antioxidants, plant foods, and healthy fats.

Chocolate is a potential acne trigger in some patients, but the research is mixed due to difficulty separating chocolate from sugar and dairy. One interesting study compared milk chocolate with jellybeans (standardized to have the same glycemic load as the chocolate) and found that the chocolate group participants had higher acne rates. More research is needed in this area, but many patients self-report chocolate as an acne trigger at the clinical level.

Supplementation

Topical and oral supplementation can be a helpful addition to a comprehensive acne treatment plan. One important note is that patient education around supplementation is key, with emphasis placed on long-term health management as opposed to a short-term curative protocol. The following oral supplement options have been shown to reduce acne progression:

- Zinc supplementation between 15-50mg/day provides antioxidant support

- Saw palmetto may aid in the inhibition of 5a-reductase and minimize symptoms of hyperandrogenism

- Probiotics to offset increased p. acnes level and to promote a healthy microbiome, decrease inflammation, and decrease sebum production

- Green tea extract for inflammation and antioxidant support

- Omega-3 fatty acids 1000mg/day to decrease mTORC levels and reduce systemic inflammation

There are a wide variety of topical treatments available as well. Both 1% and 5% topical green tea extract has been found to be comparable to 1% clindamycin and was significantly effective in reducing total acne lesions and inflammation. Topical 4% niacinamide has also been found to reduce acne progression.

Summary

A thorough history and laboratory evaluation for underlying neuroendocrine disorders is important in the management of acne and includes clinical signs and comprehensive laboratory evaluation. Dietary interventions including reducing diary, chocolate, high glycemic index foods, and following a Mediterranean style diet all work to decrease mORC1, IGF-1, and increase Fox01 activity. Oral and topical supplementation can reduce acne including zinc, probiotics, green tea extract, niacinamide, and omega-3s. Prioritizing specific patient risk factors and modulating expectations for long-term management can help patients navigate this complex condition and lead to clearer and healthier skin overall.

References:

- Bagatin, E., de Freitas, T. H. P., Machado, M. C. R., Ribeiro, B. M., Nunes, S., & da Rocha, M. A. D. (2019). Adult female acne: A guide to clinical practice. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia, 94(1), 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198203

- Clayton RW, Langan EA, Ansell DM, de Vos IJHM, Göbel K, Schneider MR, Picardo M, Lim X, van Steensel MAM, Paus R. Neuroendocrinology and neurobiology of sebaceous glands. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2020 Jun;95(3):592-624. doi: 10.1111/brv.12579. Epub 2020 Jan 22. PMID: 31970855.

- Elsaie ML. Hormonal treatment of acne vulgaris: an update. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016 Sep 2;9:241-8. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S114830. PMID: 27621661; PMCID: PMC5015761.

- Jović, A., Marinović, B., Kostović, K., Čeović, R., Basta-Juzbašić, A., & Bukvić Mokos, Z. (2017). The Impact of Pyschological Stress on Acne. Acta Dermatovenerologica Croatica: ADC, 25(2), 1133–1141.

- Tanghetti EA. The role of inflammation in the pathology of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013 Sep;6(9):27-35. PMID: 24062871; PMCID: PMC3780801.

- Melnik, B. C., & Zouboulis, C. C. (2013). Potential role of FoxO1 and mTORC1 in the pathogenesis of Western diet-induced acne. Experimental Dermatology, 22(5), 311–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/exd.12142

- Juhl, C. R., Bergholdt, H. K. M., Miller, I. M., Jemec, G. B. E., Kanters, J. K., & Ellervik, C. (2018). Dairy Intake and Acne Vulgaris: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 78,529 Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. Nutrients, 10(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10081049

- Melnik BC. Lifetime Impact of Cow’s Milk on Overactivation of mTORC1: From Fetal to Childhood Overgrowth, Acne, Diabetes, Cancers, and Neurodegeneration. Biomolecules. 2021 Mar 9;11(3):404. doi: 10.3390/biom11030404. PMID: 33803410; PMCID: PMC8000710.

- Delost GR, Delost ME, Lloyd J. The impact of chocolate consumption on acne vulgaris in college students: A randomized crossover study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Jul;75(1):220-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1159. PMID: 27317522.

- Cervantes, J., Eber, A. E., Perper, M., Nascimento, V. M., Nouri, K., & Keri, J. E. (2018). The role of zinc in the treatment of acne: A review of the literature. Dermatologic Therapy, 31(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.12576

- Goodarzi A, Mozafarpoor S, Bodaghabadi M, Mohamadi M. The potential of probiotics for treating acne vulgaris: A review of literature on acne and microbiota. Dermatol Ther. 2020 May;33(3):e13279. doi: 10.1111/dth.13279. Epub 2020 Apr 7. PMID: 32266790.

- Jung JY, Kwon HH, Hong JS, Yoon JY, Park MS, Jang MY, Suh DH. Effect of dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acid and gamma-linolenic acid on acne vulgaris: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014 Sep;94(5):521-5. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1802. PMID: 24553997.

- Kim, S., Park, T. H., Kim, W. I., Park, S., Kim, J. H., & Cho, M. K. (2021). The effects of green tea on acne vulgaris: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Phytotherapy Research: PTR, 35(1), 374–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6809

- Yoon JY, Kwon HH, Min SU, Thiboutot DM, Suh DH. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate improves acne in humans by modulating intracellular molecular targets and inhibiting P. acnes. J Invest Dermatol. 2013 Feb;133(2):429-40. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.292. Epub 2012 Oct 25. PMID: 23096708.

- Khodaeiani E, Fouladi RF, Amirnia M, Saeidi M, Karimi ER. Topical 4% nicotinamide vs. 1% clindamycin in moderate inflammatory acne vulgaris. Int J Dermatol. 2013 Aug;52(8):999-1004. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12002. Epub 2013 Jun 20. PMID: 23786503.