Dr. Liz Bartman

Hair loss is a common concern affecting millions of people worldwide. As medical professionals, understanding the evaluation process for hair loss is crucial in providing accurate diagnoses and developing effective treatment plans.

When a patient presents to your office with a concern of hair loss, you want to begin with a thorough medical history and physical examination. The following points should be addressed:

- Onset and Progression: Determine the time of hair loss onset and its progression over time. This information can help differentiate between acute and chronic conditions.

- Pattern of Hair Loss: Observe the pattern of hair loss, such as androgenetic alopecia (male or female pattern), alopecia areata (balding spots or patchy hair loss), or telogen effluvium (diffuse hair loss).

- Associated Symptoms: Inquire about symptoms like itching, burning, or pain in the scalp, as these may suggest underlying conditions or infections.

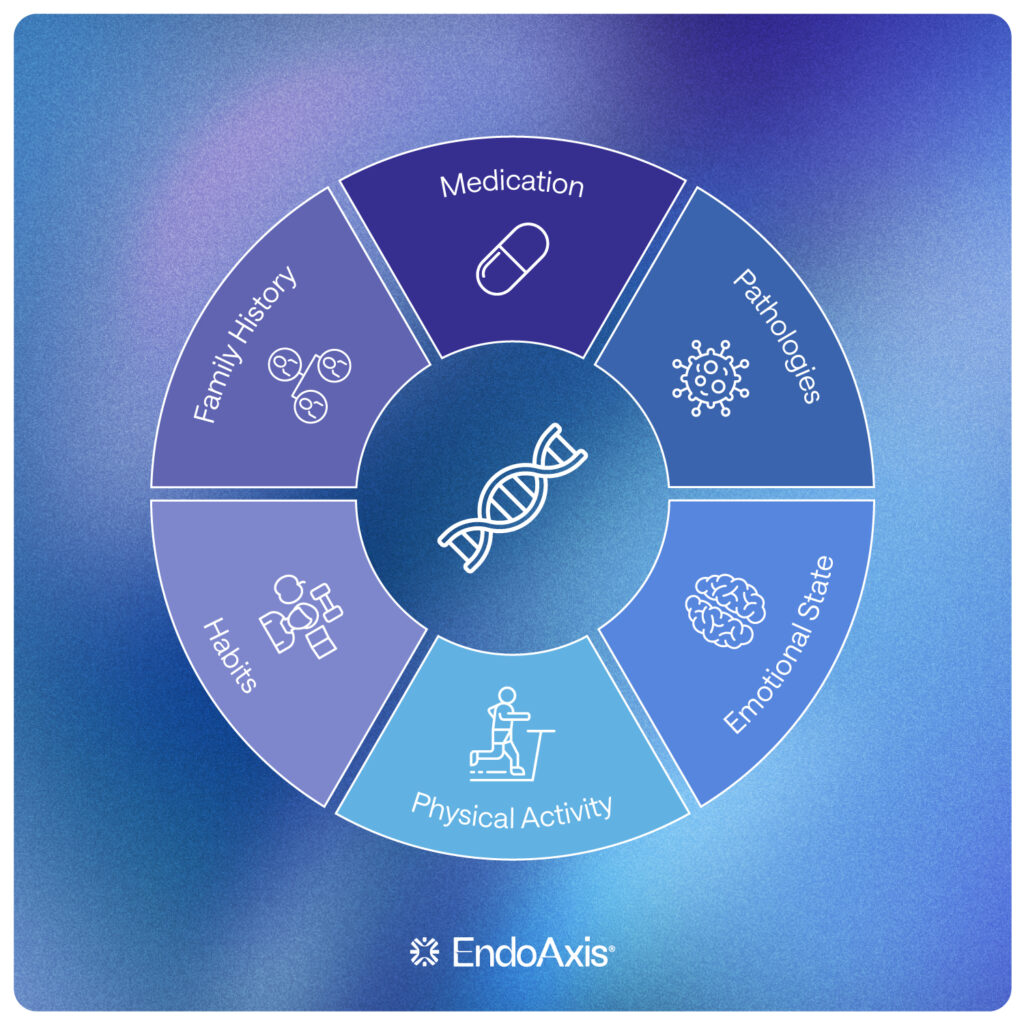

- Medical and Family History: Explore the patient’s medical history, including any autoimmune diseases, thyroid disorders, hormonal imbalances, or genetic predispositions to hair loss.

- Medications and Supplements: Determine if the patient is taking any medications or supplements that might contribute to hair loss as a side effect.

Laboratory Investigations:

Based on the patient’s history and examination, further laboratory investigations may be necessary to identify potential underlying causes:

- Complete Blood Count: Evaluate for anemia or other blood abnormalities that can contribute to hair loss.

- Thyroid Function Tests: Assess thyroid hormone levels to rule out thyroid disorders.

- Hormonal Assays: Measure androgen and estrogen levels, especially in women, to identify hormonal imbalances that may cause hair loss.

- Autoimmune Panel: Conduct tests for autoimmune conditions like systemic lupus erythematosus or alopecia areata.

- Iron Studies: Check serum ferritin levels to assess iron stores, as iron deficiency can lead to hair loss.

Specialized Testing:

- Dermoscopy and Scalp Biopsy:

- Dermoscopy, a non-invasive technique, allows for close examination of the scalp and hair follicles. It aids in diagnosing specific types of hair loss, such as alopecia areata or androgenetic alopecia. In some cases, a scalp biopsy may be necessary to obtain a definitive diagnosis. The biopsy can help differentiate between scarring (cicatricial) and non-scarring (non-cicatricial) types of hair loss.

- Fungal Culture:

- Performed by taking a skin scrapping of the scalp, especially over any areas that appear red, scaly, yellow, crusty or excessively oily. This will help identify if there is a fungal culprit to the hair loss, most often caused by tinea capitis.

- Pull test:

- Collect a bundle of hair, as though you were to pull the hair into a pigtail, and gently pull or tug the hair to see if strands come out easily. This identifies telogen effluvium, a very common cause for hair loss often as a result of a recent stressor (psychological, physical or even dietary like a restricted diet)

- Trichogram:

- Assessing the roots of the hair under a microscope to determine the hair cycle.

How the DUTCH test could help:

There are a few markers that can help identify potential causes of hair loss on a DUTCH sex hormone panel.

Androgenic hair loss could be identified if you are seeing elevated:

- 5a-DHT and 5a-Androstendiol

- 5a-Androstendiol is actually a more sensitive and accurate marker for androgenic activity at a cellular level, as it is formed only when DHT has been active on a cell receptor.

Another marker to review is cortisol.

- High cortisol metabolism can indicate a stress connection to hair loss.

- Low cortisol metabolism could indicate a concern for thyroid imbalance or mitochondrial concerns resulting in poor proteins synthesis and hair loss.

The DUTCH also provides b-hydroxyisovalerate, a biotin marker reflected on their Organic Acid Metabolites page. When elevated, there is a strong correlation with low biotin levels. As biotin is critical for a healthy hair growth cycle, high b-hydroxyisolvalerate could be used to determine if a biotin deficiency is playing a role in your patients hair loss.

The Hair Cycle:

When assessing hair loss, it is important that you understand the physiology of hair growth. Hair follows cycles and requires appropriate nutrients, hormone balance, and gene signaling to continue its cycle. There are genetic predispositions for hair loss that essentially shorten the anagen stage of the hair growth cycle, resulting in thinner and shorter hair over time. This happens naturally as we age as well (our cell division slows down). Hormone imbalances can have a similar impact on the anagen cycle, and can be impacted by genetics or environmental factors.

A healthy scalp can shed 50-100 hair strands per day. In fact, shedding is a routine and natural part of the hair growth cycle.

The cycle starts with late anagen phase that lasts often around 2-6 years in length. This is the growth and maturation phase.

The Catagen phase is follicle rest and protein release. This lasts about 2-4 weeks. This is when significant shedding occurs.

Then the Telogen phase, a new follicle is coming to life, pushing out the remaining old follicle and residual hair. This is often when the bulk of our hair falls out in mass. As it sheds, it is being replaced by new hair. This can last 3-5 months.

Then the early anagen phase, when hair takes root, and starts to grow into a mature protein.

The Catagen phase is triggered under times of stress, and new significant hair loss follows (Telogen) when the hair is starting to get back into recovery.

When there is a sudden thinning diffuse throughout the scalp, it may be:

- A part of a healthy hair cycle. Usually, every 3-5 years or so we lose a significant amount of hair. So long as new hair comes in and we notice our hair return to prior thickness within 3 months, we’re good.

- A result of a major stress that blunted the Catagen phase and caused hair to go into a premature stall and rest cycle (telogen effluvium). This can be physical stress like a major illness, a major psychologic stress, a recent drastic dietary change (like going keto or vegan), significant caloric restriction, gastric bypass surgery, pregnancy or even poor stomach acid resulting in poor protein absorption. The stalled rest cycle is followed by the Telogen phase with massive hair loss. This is marked by global hair loss (not patchy, but just all the scalp is shedding- around 30-50% of hair will be lost in these cycles). You will also see a positive “pull test” – which means if you run your fingers through their hair or gently tug a small bundle of hairs, you come out with hair in your fingers as the current follicle is being replaced, so the hair just falls out more easily as there is no anchor. There can be a nutrient deficiency impairing the next round of hair growth from being as robust. Iron, vitamin E, CoQ10, zinc, selenium and biotin are the critical nutrients needed for hair growth, while adequate protein is required for general hair synthesis.

- There is a hormonal imbalance resulting in a shorter Anagen phase. Check in on DHT and 5a-androstendiol levels as well as thyroid markers to ensure hormones are appropriately balanced. Of important note, DHT can be active in the hair follicle and NOT elevated systemically. If you suspect androgens are a culprit of hair loss, yet do not see elevated DHT in serum, or an elevation of 5a-DHT or 5a-Androstendiol on a DUTCH test, it does not mean they don’t have high DHT within the follicle proper. A biopsy can help identify DHT levels within the follicle.

- There was a recent chemotherapeutic used. This is called Anagen effluvium, and results in altered hair synthesis and growth, leading to more brittle hair with a shorter growth cycle (so greater loss over time).

- There is an autoimmune process. Hypo and Hyper-thyroid states and connective tissue disorders like Sjogren’s, Lupus, and Scleroderma can all result in shorter anagen phase and poor protein synthesis.

If the thinning occurs in localized spots, there may be more concern for:

- Alopecia areata – an autoimmune disorder specifically damaging hair follicles and prevents growth.

- Tinea capitis – fungal infection damaging hair follicle response and hair growth.

- Mechanical culprits – hair processing, tight hair styles, and excess use hair sprays/dyes/chemicals can all damage hair proteins and can result in patchy hair loss in areas of high constriction, or even diffuse hair loss if the chemical treatments are diffuse.

- Psychological factors – trichotillomania is defined as a strong urge to pull out one’s hair. It is often associated with underlying anxiety, depression or obsessive-compulsive conditions. You may see patches of hair loss that are more random in location, with hair follicles that look broken or torn.

- Psoriasis – Psoriasis is an inflammatory skin condition that can result in plaques generally on the extensor surfaces of the body. This can include the scalp. If the plaques are extensive, they can damage the follicles and impair hair growth.

If they have lost all their hair, and have not been on a chemotherapeutic agent, then this would be a concern for a genetic condition called Alopecia totalis/universialis. A work-up and treatment through dermatology is recommended.

The two most common causes of hair loss are stress-induced telogen effluvium, and androgenic alopecia (caused by higher DHT activity in the hair follicle, often driven by genetics).

If labs rule out higher androgens, remember, a biopsy may still be necessary if you suspect an androgenic culprit. Androgenic hair loss will not have a positive pull test – it is well anchored; it just has a shorter growth cycle.

Along with your detailed labs and physical examination, as a part of your history, it is important to ask, “What happened around 3-4 months ago?” If there was a major stress, illness, surgery, delivery of a child, diet change or medication change 3-4 months prior to the hair shedding, that most likely caused the hair cycle to shorten and the Telogen phase to trigger (to rest and reset). Additionally, if you find that their hair comes out in your fingers, it is likely telogen effluvium.

Hair loss evaluation requires a systematic approach encompassing patient history, physical examination, laboratory investigations, specialized tests, and even possible collaboration with specialists. By understanding the various causes and diagnostic methods, medical professionals can accurately diagnose hair loss conditions and provide appropriate treatment options to their patients. Early intervention and a multidisciplinary approach contribute to improved patient outcomes and overall satisfaction.

References

- Dhurat R, Saraogi P. Hair evaluation methods: merits and demerits. Int J Trichology. 2009;1(2):108-119.

- Wang TL, Zhou C, Shen YW, et al. Prevalence of androgenetic alopecia in China: a community-based study in six cities. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(4):843-847.

- Shapiro J. Clinical practice. Hair loss in women. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(16):1620-1630.

- Mounsey AL, Reed SW. Diagnosing and treating hair loss. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(4):356-362.

- Banka N, Bunagan MJ, Shapiro J. Pattern hair loss in men: diagnosis and medical treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31(1):129-140.

- Gordon KA, Tosti A. Alopecia: evaluation and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2011;4:101-106.

- Alkhalifah A. Alopecia areata update. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31(1):93-108.

- Kumaresan M. Intralesional steroids for alopecia areata. Int J Trichology. 2010;2(1):63-65.

- Gilhar A, Etzioni A, Paus R. Alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(16):1515-1525.

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Farrand N, Schuenemann E, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: the CAPITIS study. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):966-973.

- Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide to Common Skin Disorders: Diagnosis and Management. 3d ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:323.

- Franklin ME, Flessner CA, Woods DW, et al.; Trichotillomania Learning Center-Scientific Advisory Board. The child and adolescent trichotillomania impact project: descriptive psychopathology, comorbidity, functional impairment, and treatment utilization. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29(6):493-500.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, Neuhaus IM, eds. Diseases of the skin appendages. In: Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Elsevier; 2016:747–788.

- Mubki T, Rudnicka L, Olszewska M, Shapiro J. Evaluation and diagnosis of the hair loss patient: part I. History and clinical examination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(3):415.e1-415.e15.

- Lurie R, Hodak E, Ginzburg A, David M. Trichorrhexis nodosa: a manifestation of hypothyroidism. Cutis. 1996;57(5):358-359.

- Trüeb RM. Chemotherapy-induced alopecia. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28(1):11-14.

- Kanwar AJ, Narang T. Anagen effluvium. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79(5):604-612.

- McGarvey EL, Baum LD, Pinkerton RC, Rogers LM. Psychological sequelae and alopecia among women with cancer. Cancer Pract. 2001;9(6):283-289.

- Münstedt K, Manthey N, Sachsse S, Vahrson H. Changes in self-concept and body image during alopecia induced cancer chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 1997;5(2):139-143.

- Springer K, Brown M, Stulberg DL. Common hair loss disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(1):93-102.

- Thiedke CC. Alopecia in women. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(5):1007-1014.